As monsoon showers begin to ease across large parts of southern India, communities along the Krishna River basin are still facing rising waters. Surprisingly, this surge is not a result of local rainfall but rather of massive dam discharges from Maharashtra. This complex and alarming situation underscores the interconnected nature of river systems, where rainfall in one state can have life-altering consequences hundreds of kilometers away.

In this detailed blog, we’ll unpack the reasons why the Krishna River continues to swell despite reduced rainfall, examine the challenges faced by Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, and explore the broader implications for people, agriculture, infrastructure, and regional cooperation.

A Tale of Two Realities: Rainfall Subsides, but Floods Persist

Rainfall Drops, But Waters Keep Rising

Monsoon rains in Karnataka have begun to weaken, providing much-needed relief to saturated soils and waterlogged villages. Yet, this hasn’t translated into lower river levels. The Krishna remains swollen as upstream reservoirs in Maharashtra release massive volumes of water to manage their own surging inflows.

For instance, authorities reported that over 1.5 lakh cusecs of water flowed into Karnataka from Maharashtra, while downstream releases included 1.2 lakh cusecs from Hippargi dam and 2.5 lakh cusecs from the Almatti reservoir. This heavy discharge created a chain reaction, swelling tributaries and submerging infrastructure in flood-prone districts.

Why the Disconnect?

Normally, river levels begin to stabilize once rainfall reduces. However, this year, the situation is different. Torrential rainfall in Maharashtra’s ghats—where some locations recorded upwards of 500 mm of rain within 24 hours—poured directly into reservoirs that had already reached capacity. To prevent dam breaches, engineers were left with no choice but to release water downstream, even as local rainfall eased.

Maharashtra’s Downpour: The Root Cause of Overflow

Regions such as Tamhini and Lonavala in Maharashtra experienced extreme rainfall episodes that funneled water into the Krishna’s catchment. The deluge overwhelmed storage capacities, pushing dam operators to open floodgates. While this safeguarded upstream structures, it transferred the flood risk to downstream areas in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

This chain reaction demonstrates the ripple effect of river basin hydrology—where upstream weather events translate into downstream emergencies.

Regional Impacts: Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh

Karnataka: Battling Flood Emergencies

In Karnataka’s Belagavi district, swelling tributaries like the Vedganga and Doodhganga spilled over their banks, submerging bridges and isolating entire communities. Authorities established more than 500 relief centers to shelter displaced families, while rescue teams from the State and National Disaster Response Forces were deployed.

Vijayapura and Bagalkot districts faced similar challenges. With 2.5 lakh cusecs being discharged from Almatti dam, precautionary evacuations became necessary. Families in low-lying areas were relocated as roads, fields, and residential areas were inundated.

The impact extended beyond infrastructure. Schools in vulnerable taluks were closed, agricultural land was submerged, and hundreds of homes suffered water damage.

Andhra Pradesh: Tourism and Urban Challenges

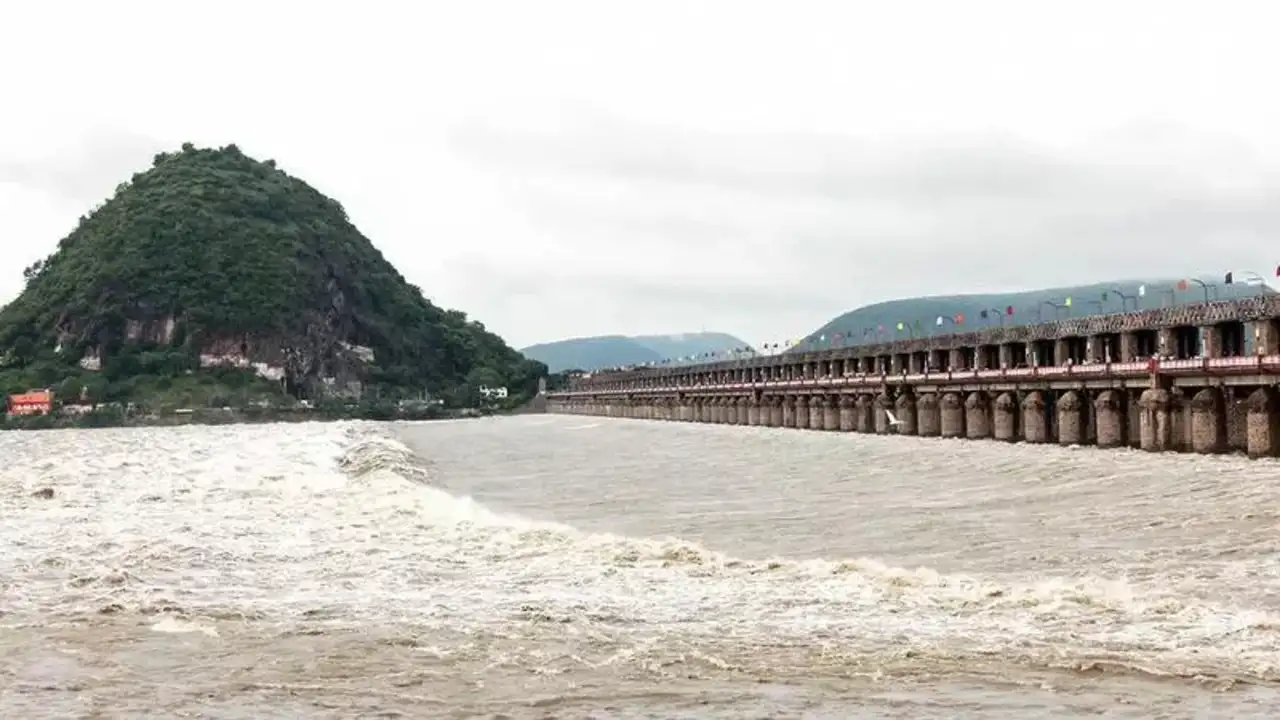

Further downstream, Andhra Pradesh felt the compounded effects. Vijayawada’s popular tourist destination, Bhavani Island, had to be closed to visitors as floodwaters rose dangerously. The suspension of boating and tourism activities led to economic losses running into tens of lakhs of rupees.

At the Prakasam Barrage, flood discharge escalated dramatically, surging from about 2.5 lakh cusecs to more than 4.3 lakh cusecs in less than 24 hours. Authorities responded by sounding high alerts, opening nearly 40 relief shelters, and evacuating residents from vulnerable wards across the city.

Human, Agricultural, and Economic Toll

Disrupted Lives

Floodwaters submerged hundreds of homes in Belagavi and neighboring districts. Families were forced to leave behind belongings and livestock as they sought safety in relief camps. For many, the floods have brought back painful memories of previous calamities, where recovery took months or even years.

Agricultural Damage

Standing crops—especially sugarcane, maize, and paddy—have been badly hit. Farmers face the dual burden of immediate crop losses and long-term soil degradation caused by waterlogging. Livelihoods in agrarian belts along the Krishna basin hang in the balance as compensation and relief measures are rolled out.

Tourism and Economy

Beyond homes and farms, the region’s economy has taken a hit. Tourism revenue, particularly in Vijayawada, dropped significantly due to the suspension of water-based activities. Daily wage earners, transport operators, and hospitality businesses connected to tourism now face uncertainty.

Why Does This Keep Happening? The Role of Dam Management

The Coordination Problem

Experts point out that while dams are designed to regulate water flow, poor coordination between riparian states often makes flooding worse. When releases are delayed and then suddenly executed in large volumes, downstream districts are hit by a surge they cannot prepare for.

This is not a new phenomenon. Historical floods in the Krishna basin—including major ones in 2009 and 2024—were linked to uncoordinated reservoir management. Despite repeated warnings, a standardized, interstate water release protocol remains elusive.

What Needs to Change?

- Forecast-Based Releases: Rather than sudden, emergency releases, dam authorities should follow predictive rainfall and inflow models to make gradual adjustments.

- Interstate Coordination: Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh must share real-time data and synchronize dam operations to reduce flood risks.

- Infrastructure Upgrades: Embankments, bridges, and flood defenses must be reinforced to withstand repeated high-flow events.

- Community Preparedness: Early-warning systems and community awareness campaigns can ensure quicker evacuations and reduce human losses.

Lessons from the Crisis

This ongoing crisis teaches us that managing floods is not just about responding to rainfall but also about controlling how stored water is released. As climate change increases the frequency of extreme rainfall events, such crises may become more common unless long-term solutions are put in place.

Climate Change Connection

The intensity of rainfall in Maharashtra’s ghats aligns with global patterns of shifting monsoons and more erratic weather. Such extreme downpours overwhelm reservoirs faster than before, highlighting the urgent need for adaptive water management strategies.

Looking Ahead: Building Resilience in the Krishna Basin

To minimize future disasters, policymakers, engineers, and local authorities must focus on:

- Integrated River Basin Management: A holistic approach where all riparian states plan and act together, treating the river as a shared system.

- Data-Driven Decision Making: Leveraging satellite data, AI-based forecasting, and real-time monitoring to inform dam operations.

- Disaster-Resilient Infrastructure: Flood-resistant roads, elevated bridges, and stronger embankments to minimize damage during high-flow periods.

- Community-Centered Relief: Relief and rehabilitation programs should not only address immediate displacement but also long-term livelihood restoration.

Conclusion

The ongoing floods along the Krishna River are a stark reminder that reduced rainfall doesn’t automatically mean reduced flood risk. The rising waters are being fueled by upstream dam discharges in Maharashtra, creating ripple effects downstream in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

For communities along the basin, this disconnect between easing skies and swelling rivers has brought hardship, economic loss, and uncertainty. It also underscores the urgent need for better coordination, predictive management, and long-term resilience planning.

In the end, managing floods is not just about responding to what falls from the sky—it’s about managing what flows from it. The Krishna basin crisis makes one thing clear: until upstream and downstream states work in unison, the cycle of floods will continue to repeat, year after year.